Scientists have confirmed what happened to a star born in a stunning supernova visible from Earth more than thirty years ago: it turned into a neutron star, one of the world's largest and strangest objects in the universe.

In 1987, a star exploded in a nearby galaxy, turning into a supernova, and its fiery end was observed with the naked eye in the Earth’s night sky for several months. Scientists believed that when the star's core collapsed, the remains would turn into one of two things: a black hole from which nothing could escape, or a neutron star, which is the densest body in the universe outside the black hole.

The problem was that there was so much debris that astronomers couldn't see it beyond the dust. But NASA's Webb Space Telescope cut to the chase by looking into infrared light and discovering two chemical signatures — argon and sulfur — of an ultra-hot neutron pulsar, suggests a study published Thursday in the journal Science.

Because the explosion is recent and well-documented, the discovery should help astronomers better understand this type of cosmic anomaly and its predecessors that helped seed the universe with important elements like carbon and iron.

This neutron star is only 20 kilometers from end to end, but it weighs one and a half times as much as our Sun. It is very dense, and there is not much space between the different parts of its atoms. According to scientists, Supernova 1987A may be the only time modern astronomy has been able to observe the birth and early years of a neutron star, although there are other closer but older stars in our galaxy.

“Along with the black hole, these are the most exotic objects in the universe,” said lead author Claes Fransson, an astrophysicist at Stockholm University in Sweden. “We've known about these objects since the 1960s, but we've never seen one actually form before.”

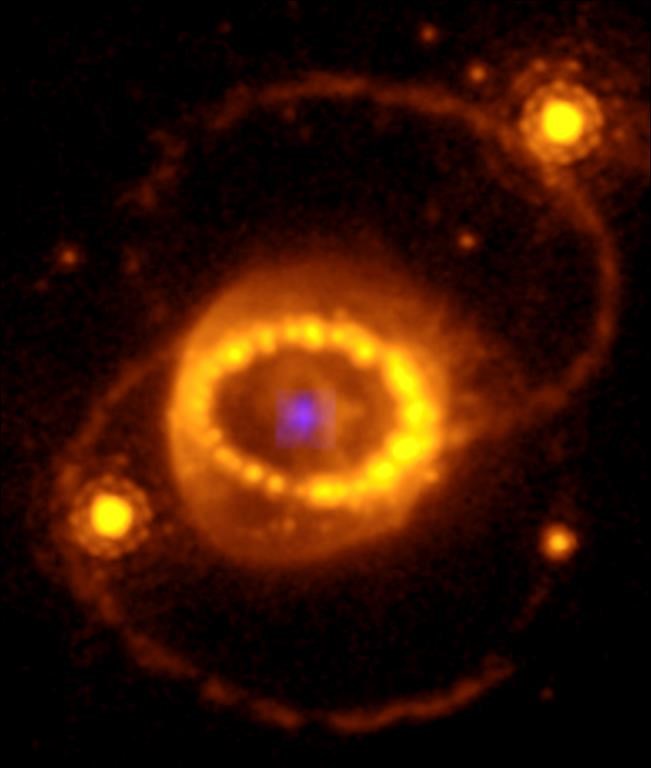

Images of the distant supernova remnant show what Franson calls a “ring of pearls” surrounding a cloud of dust. And somewhere in the dust is a neutron star.

Scientists had long suspected that the collapsed core turned into a neutron star. But this measurement by the Webb telescope, even if it is not a direct image of the neutron star, provides a fairly definitive answer, according to Mr. Franson and other scientists.

Roger Blandford, an astrophysicist at Stanford University who was not involved in the study, believes the neutron star arguments have merit.

Because the supernova explosion is so recent and so close, it is “a gift that keeps on giving, teaching us things about neutrinos, stellar evolution, and now what happens after the explosion,” Mr. Blandford said in an email.